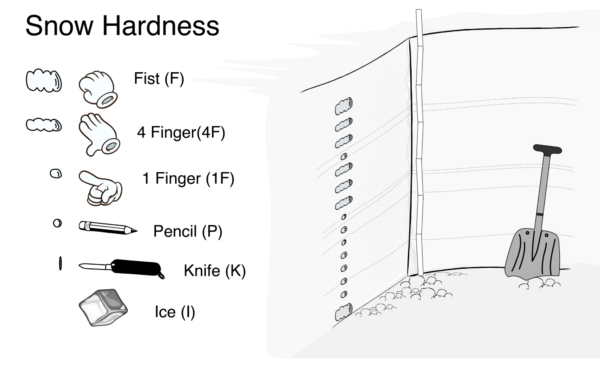

Snow's resistance to pressure is a proxy for strength, measured by pushing objects into snow layers.

Assessing the relative hardness of layers within the snowpack is valuable for detecting the presence and strength of slabs and weak layers. Hardness, or the resistance of snow to pressure, is a proxy for the strength of a snow layer. We categorize hardness using the hand hardness scale using the same relative amount of force to push various objects into the snow. How much force? Push your closed fist into your nose until it feels uncomfortable; that is roughly the amount of force you should use. Hardness ranges from very low, where you can push your fist easily into the snow, to ice hard, which is too hard to push a knife into. Hard snow on top of soft snow is considered poor structure; the more dramatic and sudden the change in hardness, the more concerning it is. For example, a pencil hard slab over a fist hard layer of depth hoar is a scary structure!

- Fist hardness (F) If a gloved fist pushes into the snow with moderate force, it has a very low hardness. Common examples of fist hard snow include the most fragile weak layers, such as surface hoar, depth hoar, or fresh powder snow that gives you the best faceshots. Fist hard snow is commonly a weak layer or becomes entrained in loose dry sluffs.

- 4 Finger hardness (4F) If four gloved fingers push into the snow with moderate force, it has a low hardness. Common examples of four finger hard snow include storm snow that has settled for a few days, new snow affected by just a small amount of wind, and faceted weak layers that have been buried for a few weeks. Four finger snow can be both a soft slab and a weak layer depending on the surrounding structure.

- 1 Finger hardness (1F) If a gloved index finger pushes into the snow with moderate force, it has a medium hardness. Common examples of one finger hard snow include rounded snow grains that have been buried and settled for a few weeks, or recent snow that has been moderately affected by the wind. One finger snow marks the transition towards hard slabs which produce denser, chunkier debris. Although one finger snow is commonly a slab, it can also act as a weak layer for deep, hard slabs.

- Pencil hardness (P) If the blunt end of a pencil pushes into the snow with moderate force, it has a high hardness. Common examples of pencil hard snow include rounded snow grains that are buried by a deep snowpack, crusts, or storm snow that has been impacted by an extreme wind event. Pencil hard snow is usually associated with a hard slab or a bed surface.

- Knife hardness (K) If a knife blade pushes into the snow with moderate force, it has a very high hardness. Common examples of knife hard snow include hard crusts or very small, rounded grains near the bottom of a deep snowpack. Knife hard snow can act as a bed surface or make up part of a hard slab.

- Ice hardness (I) If the snow is too hard to push a knife into with moderate force, it is ice hard. Common examples of ice hard snow include lenses or vertical columns of ice where liquid water has frozen, or very hard crusts that you can’t kick a boot through. Ice layers commonly act as bed surfaces or they can serve to strengthen the snowpack when they form vertical columns.