A fragile weak layer notorious for surprising behavior and persistent instabilities.

Surface hoar develops as feathery crystals on the snow surface if the air above it is cooled to the frost point. The recipe for effective surface hoar growth is rather specific: a clear, cold sky, a high relative humidity, and relatively calm winds. When these conditions come together, surface hoar can form very quickly, just like the frost on your windshield. It is equally challenging for these fragile feathers to survive on the snow surface. Wind, rain, sun, or sluffs can easily destroy surface hoar before it gets buried. Thus, the spatial patterns of a buried surface hoar layer can be fickle and “pockety”. You may find it in one bowl but not the next. You may find it in one snowpit but not the next, 10 yards away. The ingredients for the formation and preservation of surface hoar most often come together in sparsely gladed or open, wind-protected terrain on colder aspects, well below windy ridges and mountain tops–the same type of terrain that you might overlook as an obvious starting zone. It is also common for surface hoar to form on a specific elevation band. This pattern is often referred to as the “bathtub ring” effect. Carefully tracking the formation and location of preserved surface hoar before it gets buried is the best strategy for avoiding the problems it causes in the future. Once buried, it gets harder to identify problematic slopes. You might be able to identify buried surface hoar layers as a thin, grey stripe in a snowpit or pick them out in a snowpack test, but again, the presence and absence of this layer can be highly variable. Buried surface hoar can cause Persistent Slab instabilities for months, and it is a common weak layer in avalanche accidents.

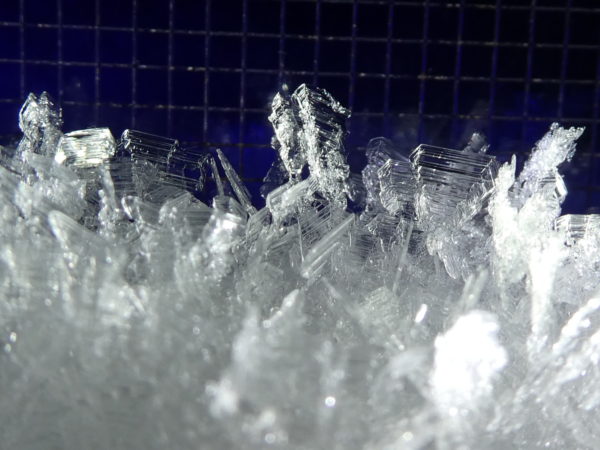

Surface hoar grows quickly on the snow surface under a clear, cold sky, a high relative humidity, and relatively calm winds. Credit: Crested Butte Avalanche Center

Buried surface hoar may present as a thin, grey stripe in the snowpack. Credit: Crested Butte Avalanche Center

When low stratus or fog layers develop under clear skies, surface hoar commonly forms a “bathtub ring” distribution near the boundary of the clouds. Credit: Crested Butte Avalanche Center

Because surface hoar is easily destroyed by wind, it is most commonly preserved in wind sheltered terrain with incoming storms. Thus, the most troublesome terrain for a buried surface hoar layer may not be classic alpine start zones, but rather, sparsely gladed slopes lower on a mountain. Credit: Crested Butte Avalanche Center