Layers of the snowpack gaining strength as snow grains weld together.

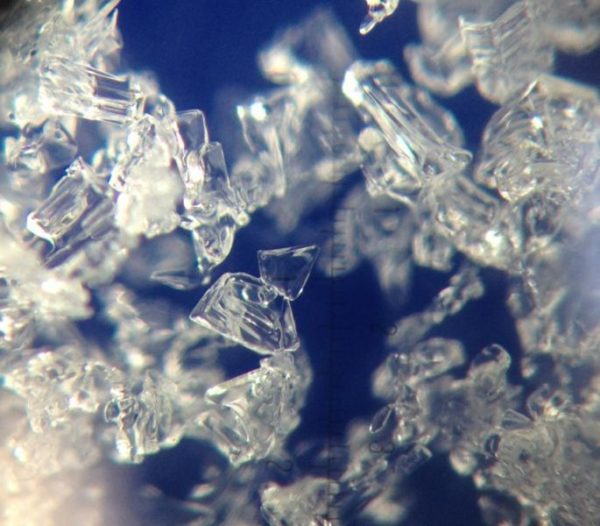

Bonding describes snow grains forming stronger bonds with one another both within a layer and also between adjacent layers. Dry snow grains bond together from wind breaking down snow grains, mechanical compaction, grain boundary diffusion, and rounding due to water vapor movement. Under low vapor pressure gradients, water vapor is deposited at the concave contact points between snow grains and fortifies their bonds. You can see these bonds, called “necks”, by using a hand lens. Sintering or bonding of the snow happens more readily in deep snowpacks and when temperatures are relatively mild. The process is temperature dependent and is much slower during exceptionally cold temperatures. The snowpack stability improves as weak layers sinter or bond. For layers in the upper few feet of the snowpack, stability tests provide general information on how well the snowpack might be bonding. The deeper the layer of concern, the less informative these observations become. Observing layer hardness, grain shape, and grain size can further inform the general trend of bonding.

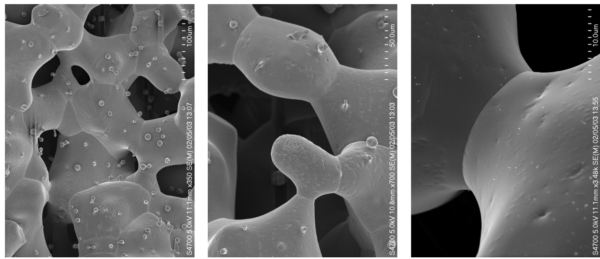

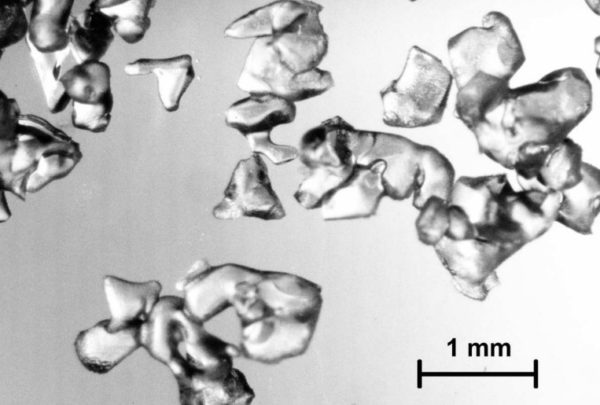

Small grained facets that are now bonding together, evidenced by necks forming between the snow crystals. Credit: The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground / AINEVA UniMilano

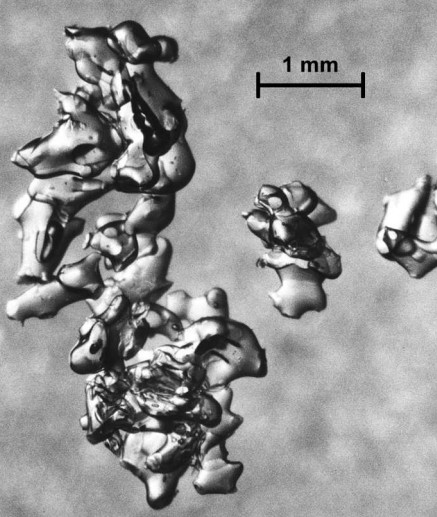

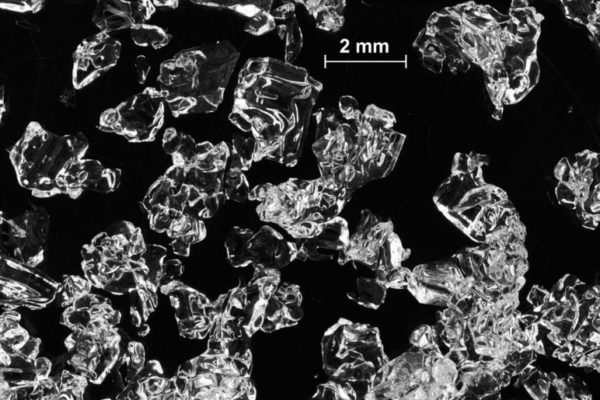

Large grained facets that are sintering and bonding together. Within the snowpack, these grains changed from a faceting environment to a rounding environment. Credit: The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground / Elder