A relatively hard and slick layer (a crust) with a faceted persistent weak layer above or below.

Crusts that form early season or mid-winter often develop weak facets above or below them. Crusts can promote faceting and inhibit normal bonding processes after the layer gets buried; thus a faceted crust can plague the snowpack for the rest of the season. Facets commonly develop around melt-freeze crusts because of the strong temperature gradients and vapor barriers associated with them. For example, snow that is wetted by rain or sun and covered by cold, dry snow will cause a very strong temperature gradient. The result after the snow refreezes is a faceted crust: weak, angular snow grains above a hard, sliding surface. Early season crusts surrounded by basal facets can be especially troublesome for Deep Persistent Slab avalanche problems later in the season. The facets may not be readily visible to the naked eye, but crusts are usually easy to identify in a snow pit by sliding a card through the snowpack to feel for their distinct hardness changes. The distribution of faceted crusts will be dictated by the rain line and/or solar input. Thus, a change in aspect, elevation, and slope angle, can influence the presence or absence of a faceted crust.

Facets developing above a sun crust. This process is called radiation recrystallization. Credit: Crested Butte Avalanche Center.

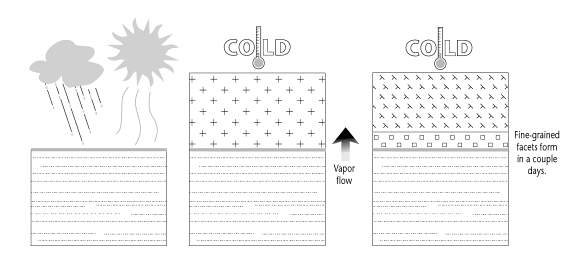

A common scenario for developing a faceted crust: warm, wet surface snow is buried by cold snow and facets because of the strong temperature gradient. This process is called melt-layer recrystallization. Credit: Bruce Tremper

Magnified view of facets that formed above a crust. Credit: The International Classification for Seasonal Snow on the Ground